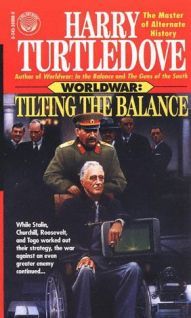

Tilting the Balance

Часть 8

Nevertheless, Molotov owed allegiance not just to Stalin, but to the Soviet Union as a whole. If he was to serve the USSR properly, he needed information. Getting it without angering his master was the trick. Carefully, he said, “The Lizards have taken a heavy toll on our bombing planes. Will we be able to deliver the bomb once we have it? ”

“I am told the device will be too heavy and bulky to fit in any of our bombers, ” Stalin said. Molotov admired the courage o-toy.ru of the man who had told-had had to tell-that to Stalin. But the Soviet leader did not seem nearly so angry as Molotov would have guessed. Instead, his face assumed an expression of genial deviousness that made Molotov want to make sure he still had his wallet and watch. He went on, “If we can dispose of Trotsky in Mexico City, I expect we can find a way to put a bomb where we want it. ”

“No doubt you are right, Iosef Vissarionovich, ” Molotov said. Trotsky had thought he was safe enough to keep plotting against the Soviet Union, but several inches of tempered steel in his, brain proved that a delusion.

“No doubt I am, ” Stalin agreed complacently. As undisputed master of the Soviet Union, he had developed ways not altogether different from those of other undisputed masters. Molotov had once or twice thought of saying as much, but it remained just that-a thought.

He did ask, “How soon can the Germans and Americans begin producing their own explosive metal? ” The Americans didn’t much worry him; they were far away and had worries closer to home. The Germans… Hitler had talked about using the new bombs against the Lizards in Poland. The Soviet Union was an older enemy, and almost as close.

“We are working to learn this. I expect we shall be informed well in advance, whatever the answer proves to be, ” Stalin answered, complacent still. Soviet espionage in capitalist countries continued to function well; many there devoted themselves to furthering the cause of the socialist revolution.

Molotov cast about for other questions he might safely ask. Before he could come up with any, Stalin bent over the papers on his desk, a sure sign of dismissal. “Thank you for your time, Iosef Vissarionovich, ” Molotov said as he stood to go.

Stalin grunted. His politeness was minimal, but then, so was Molotov’s with anyone but him. When Molotov closed the door behind him, he permitted himself the luxury of a small sigh. He’d survived another audience.

For getting his consignment of uranium or whatever it was safely from Boston to Denver, Leslie Groves had been promoted to brigadier general. He hadn’t yet bothered replacing his eagles with stars; he had more important things to worry about. His pay was accumulating at the new rate, not that that meant much, what with prices going straight through the roof.

At the moment what galled him worse than inflation was the lack of gratitude he was getting from the Metallurgical Laboratory scientists. Enrico Fermi looked at him with sorrowful Mediterranean eyes and said, “Valuable as this sample may be, it does not constitute a critical mass. ”

“I’m sorry, that’s not a term I know, ” Groves said. He knew nuclear energy could be released, but nobody had done much publishing on matters nuclear since Hahn and Strassmann split the uranium atom, and, to complicate things further, the Met Lab crew had developed a jargon all their own.

“It means you have not brought us enough with which to make a bomb, ” Leo Szilard said bluntly. He and the other physicists round the table glared at Groves as if he were deliberately holding back another fifty kilos of priceless metal.

Since he wasn’t, he glared, too. “My escort and I risked our lives across a couple of thousand miles to get that package to you, ” he growled. “If you’re telling me we wasted our time, smiling when you say it isn’t going to help. ” Even relatively lean as the journey had left him, he was the biggest man at the conference table, and used to using his physical presence to get what he wanted.

“No, no, this is not what we mean, ” Fermi said quickly. “You could not have known exactly what you had, and we could not, either, until you delivered it. ”

“We did not even know that you had it until you delivered it, ” Szilard said. “Security-pah! ” He muttered something under his breath in what might have been Magyar. Whatever it was, it sounded pungent. Groves had seen his dossier. His politics had some radical leanings, but he was too brilliant for that to count against him.

Fermi added, “The material you brought will be invaluable in research, and in combining with what we eventually produce ourselves. But by itself, it is not sufficient. ”

“All right, you’ll have to do here what you were going to do at Chicago, ” Groves said. “How’s that coming? ” He turned to the one man from the Met Lab crew he’d met before. “Dr. Larssen, what is the status of getting the project up and running again here in Denver? ”

“We were building the graphite pile under Stagg Field at the University of Chicago, ” Jens Larssen answered. “Now we’re reassembling it under the football stadium here. The work goes-well enough. ” He shrugged.

Groves gave Larssen a searching’ once-over. He didn’t seem to have the driving energy he’d shown in White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia, the summer before. Then, he’d passionately urged the federal government-in-hiding to do all it could to hold Chicago against the Lizards. But the Met Lab had had to move even though Chicago was held, and now-well, it just didn’t seem as if Larssen gave a damn. That kind of attitude wouldn’t do, not when the work at hand was so urgent.

The meeting with the physicists went on for another half hour, over lesser but still vital issues like keeping electricity coming into Denver and into the University of Denver in particular so the men could do their jobs. People in the United States had taken electricity for granted until the Lizards came. Now, over too much of the country, it was a vanished luxury. But if it vanished in Denver, the Met Lab would have to find somewhere else to go, and Groves didn’t think the country-or the world-could afford the delay.

Unlike nuclear physics, electricity was something with which, by God, he was intimately familiar. “We’ll keep it going for you, ” he promised, and hoped he could make good on the vow. If the Lizards got the idea humans were experimenting with nuclear energy here, they’d have something to say about the matter. Keeping them from finding out, then, was going to be a sizable part of keeping the lights on.

When the meeting broke up, Groves fell into step with Larssen and ignored the physicist’s efforts to break away. “We need to talk, Dr. Larssen, ” he said.

Расскажи о сайте: