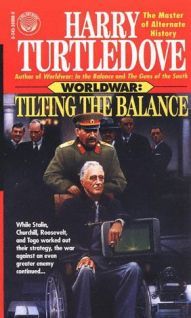

Tilting the Balance

Автор: Harry Turtledove

Издатель: Del Rey 1995

ISBN: 0345389980

Навигация: Tilting the Balance → XII

Часть 4

Ludmila nodded. Strange, she thought, that an NKVD man should talk about the rodina. From the day the Germans invaded, the Soviet government had started trotting out all the ancient symbols of Holy Mother Russia. After the Revolution, the Bolsheviks had scorned such symbols as reminders of the decadent, nationalistic past-until they needed them to rally the Soviet people against the Nazis. Stalin had even made his http://www.jazzstore.ru peace with the Patriarch of Moscow, although the government remained resolutely atheist.

Sholudenko said, “I think we can get moving again. I don’t hear the tanks any more. ”

“No, nor I, ” Ludmila said after cocking her head and listening carefully. “But you have to be careful: their machines aren’t as noisy as ours, and could be lying in wait. ”

“I assure you, Senior Lieutenant Gorbunova, I have discovered this for myself, ” Sholudenko said with sarcastic formality. Ludmila chewed on her lower lip. She had that coming-the NKVD man, having to serve on the ground, had earned the unlucky privilege of becoming intimately acquainted with Lizard hardware at ranges closer than she cared to think about. He went on, “It is, even so, a lesson which bears repeating: this I do not deny. ”

Mollified by the half apology (which was, by that one half, more than she’d ever imagined getting from the NKVD), Ludmila slid the boot back onto her foot. She and Sholudenko left the grove together and headed back toward the road. One glance was plenty to keep them walking on the verge; the column of Lizard tanks had chewed the roadbed to slimy pulp worse than the patch into which Ludmila had stumbled before. This muck, though, went on for kilometers.

Tramping along by the road wasn’t easy, either. The ground was still squashy and slippery, and the year’s new weeds and bushes, growing frantically now that warm weather and long stretches of sunlight were here at last, reached out with branches and shoots to try to trip up the travelers.

So it seemed to Ludmila, at any rate, after she picked herself up for the fourth time in a couple of hours. She snarled out something so full of guttural hatred that Sholudenko clapped his hands and said, “I’ve never had a kulak call me worse than you just gave that burdock. It certainly had it coming, I must say. ”

Ludmila’s face turned incandescent. By Sholudenko’s snicker, the blush was quite visible, too. What would her mother have said if she heard her cursing like-like… she couldn’t think of any comparison dreadful enough. Going on two years in the Red Air Force had so coarsened her that she wondered if she would be fit for anything decent when peace returned.

When she said that aloud, Sholudenko waved his arms to encompass the entire scene around them. Then he pointed at the deep ruts, already filling with water, the treads the Lizard tanks had carved in the road. “First worry if peace will ever return, ” he said. “After that you can concern yourself with trifles. ”

“You’re right, ” she said. “From where we stand, this war is liable to go on forever. ”

“History is always a struggle-such is the nature of the dialectic, ” the NKVD man said: standard Marxist doctrine. All at once, though, he turned human again: “I wouldn’t mind if the struggle were a little less overt. ”

Ludmila pointed ahead. “There’s a village. With luck, we’ll be able to lay up for a while. With a lot of luck, we’ll even find some food. ”

As they drew closer, Ludmila saw the village looked deserted. Some of the cottages had been burned; others showed bare spots in their thatches, as if they were balding old men. A dog’s skeleton, beginning to fall apart into separate bones, lay in the middle of the street.

That was the last thing Ludmila noticed before a shot rang out and kicked up mud a couple of meters in front of her. Her reflexes were good-she was down on her belly and yanking her own pistol out of the holster before she had time for conscious thought.

Another shot-she still didn’t see the flash. Her head swiveled as if on a pivot Where was cover? Where was Sholudenko? He’d hit the dirt as fast as she had. She rolled through muck toward a wooden fence. It wasn’t much in the way of shelter, but it was a lot better than nothing.

“Who’s shooting at us? And why? ” she called to Sholudenko.

“The devil’s uncle may know, but I don’t, ” the NKVD man answered. He crouched behind a well, whose stones warded him better than the fence shielded Ludmila. He raised his voice: “Hold fire! We’re friends! ”

“Liar! ” The shout was punctuated by a burst of submachine-gun fire from another cottage. Bullets sparked off the stone facing of the well. Whoever was in there yelled, “You can’t fool us. You’re from Tolokonnikov’s faction, come to run us out. ”

“I don’t have the slightest idea who Tolokonnikov is you maniac, ” Sholudenko said. All he got for an answer was another shout of “Liar! ” and a fresh hail of bullets from that submachine gun. Whomever the anti-Tolokonnikovites did favor, he gave them plenty of ammunition.

Ludmila spied the flame the weapon spat. She was seventy or eighty meters away, very long range for a pistol, but she squeezed off a couple of shots anyway, to take the heat off Sholudenko. Then, quick as she could, she rolled away. The relentless submachine gun chewed up the place where she’d been.

The NKVD man fired, too, and was rewarded by a scream and sudden silence from the submachine gun. Don’t get up, Ludmila willed at him, suspecting a trap. He didn’t. Sure enough, in a couple of minutes the gunner opened up again.

By then, Ludmila had found a boulder behind which to shelter. From that more secure position, she called, “Who is this Tolokonnikov, and what do you have against him? ” If the people who didn’t like him acted this way, her guess was that he probably had something going for him.

She got no coherent answer out of the anti-Tolokonnikovites, only another magazine’s worth of bullets from the submachine gun and a yell of, “Shut up, you treacherous bitch! ” Deadly as shell fragments, rock splinters knocked free by the gunfire flew just above her head.

She wondered how long the stalemate could go on. The answer she came up with was glum: indefinitely. There wasn’t enough cover for either side to have much hope of moving to outflank the other. She and Sholudenko couldn’t very well retreat, either. That left sitting tight, shooting every so often, and hoping you got lucky.

Then the equation suddenly grew another variable. Somebody showed himself for a moment: just long enough to chuck a grenade through the window from which the fellow with the submachine gun had been firing. A moment after it went off, he jumped in the window himself. Ludmila heard a rifle shot, then silence.

The grenade chucker came out by way of the window, too, and vanished from her sight. “Whose side is he on? ” she called to Sholudenko.

Расскажи о сайте: