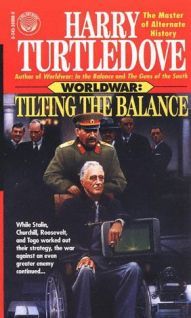

Tilting the Balance

Автор: Harry Turtledove

Издатель: Del Rey 1995

ISBN: 0345389980

Навигация: Tilting the Balance → XIV

Часть 1

Heinrich Jager gave his http://oz-mobile.ru interrogator a dirty look. “I have told you over and over, Major, I don’t know one damned thing about nuclear physics and I wasn’t within a good many kilometers of Haigerloch when whatever happened there happened. How you expect to get any information out of me under those circumstances is a mystery. ”

The Gestapo man said, “What happened at Haigerloch is a mystery, Colonel Jager. We are interviewing everyone at all involved with that project in an effort to learn what went wrong. And you will not deny that you were involved. ” He pointed to the German Cross in gold that Jager wore.

Jager had donned the garishly ugly medal when he was summoned to Berchtesgaden, to remind people like this needle nosed snoop that the Fuhrer had given it to him with his own hands: anyone who dared think him a traitor had better think again. Now he wished he’d left the miserable thing in its case.

He said, “I could better serve the Reich if I were returned to my combat unit. Professor Heisenberg was of the same opinion, and endorsed my application for transfer from Haigerloch months before this incident. ”

“Professor Heisenberg is dead, ” the Gestapo man said in a flat voice. Jager winced, nobody had told him that before. Seeing the wince, the man on the safe side of the desk nodded. “You begin to understand the magnitude of the-problem now, perhaps? ”

“Perhaps I do, ” Jager answered; unless he missed his guess, the interrogator had been on the point of saying something like “disaster, ” but choked it back just in time. The fellow had a point. If Heisenberg was dead, the bomb program was a disaster.

“If you do understand, why are you not cooperating with us? ” the Gestapo man demanded.

The brief sympathy Jager had felt for him melted away like a panzer battalion under heavy Russian attack in the middle of winter. “Do you speak German? ” he demanded. “I don’t know anything. How am I supposed to tell you something I don’t know? ”

The secret policeman took that in stride. Jager wondered what sort of interrogations he’d carried out, how many desperate denials, truer and untrue, he’d heard. In a way, innocence might have been worse than guilt. If you were guilty, at least you had something to reveal at last, to make things stop. If you were innocent, they’d just keep coming after you.

Because he was a Wehrmacht colonel with his share and more of tin plate on his chest, Jager didn’t face the full battery of techniques the Gestapo might have lavished on a Soviet officer, say, or a Jew. He had some notion of what those techniques were, and counted himself lucky not to make their intimate acquaintance.

“Very well, Colonel Jager, ” the Gestapo major said with a sigh; maybe he regretted not being able to use such forceful persuasion on someone from his own side, or maybe he just didn’t think he was as good an interrogator without it. “You may go, although you are not yet dismissed back to your unit. We may have more questions for you as we make progress on other related investigations. ”

“Thank you so much. ” Jager rose from his chair He feared irony was lost on the Gestapo man, who looked to prefer the bludgeon to the rapier, but made the effort nonetheless. The bludgeon is for Russians; he thought.

Waiting in the antechamber to the interrogation room-as if the Gestapo man inside were a dentist rather than a thug-sat Professor Kurt Diebner, leafing through a Signals old enough to show only Germany’s human foes. He nodded to Jager. “So they have vacuumed you up, too, Colonel? ”

“So they have. ” He looked curiously at Diebner. “I would not have expected you-” He paused, unable to think of a tactful way to go on.

The physicist didn’t bother with tact. “To be among the living? Only the luck of the draw, which does make a man thoughtful. Heisenberg chose to take the pile over critical when I was away visiting my sister. Maybe not all luck, after all-he might not have wanted me around to share in his moment of fame. ”

Jager suspected Diebner was right. Heisenberg had shown nothing but scorn for him at Haigerloch, though to the panzer colonel’s admittedly limited perspective, Diebner was accomplishing as much as anyone else and more than most people. Jager said, “The Lizards must have ways to keep things from going wrong when they make explosive metal. ”

Diebner ran a hand through his thinning, slicked-back hair. “They have also been doing it rather longer than we have, Colonel. Haste was our undoing. You know the phrase festina lente? ”

“Make haste slowly. ” In his Gymnasium days, Jager had done his share of Latin.

“Just so. It’s generally good advice, but not advice we can afford at this stage of the war. We must have those bombs to fight the Lizards. The hope was that, if the reaction got out of hand, throwing a lump of cadmium metal into the heavy water of the pile would bring it back under control. This evidently proved too optimistic. And also, if I remember the engineering drawings correctly, there was no plug to drain the heavy water out of the pile and so shut down the reaction that way. Most unfortunate. ”

“Especially to everyone who was working on the pile at the time, ” Jager said. “If you know all this Dr. Diebner, and you’ve told it to the authorities, why are they still questioning everyone else, too? ”

Расскажи о сайте: