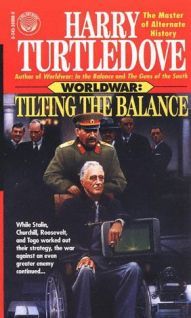

Tilting the Balance

Автор: Harry Turtledove

Издатель: Del Rey 1995

ISBN: 0345389980

Навигация: Tilting the Balance → XIV

Часть 5

“On that, if you’reverse roles, we agree completely, ” Chill said. He turned to Bagnall, gave him an ironic bow. “Congratulations. You and your British colleagues have just become a three-man board of field marshals. Shall I order your batons and have a tailor sew red stripes to your trouser seams? ”

“That won’t be necessary, ” Bagnall said. “What I need is assurance from you and from your Soviet counterparts that you’ll abide by whatever decisions we end up making. Without that, we might as well not start down this road. ”

The German general gave him a long look, then slowly nodded. “You do have some understanding of the difficulties with which you are involving yourself. I wondered if this was so. Very well, let it be as you say. By my oath as a soldier and officer of the Wehrmacht and the German Reich, I swear that I shall accept without question your decision on cases brought before you for arbitration. ”

“What about you? ” Bagnall asked the two Soviet brigadiers. Aleksandr German and Vasiliev seemed imperfectly delighted once more, but German said, “If in a dispute you rule against us, we shall accept your decision as if it came from the Great Stalin himself. This I swear. ”

“Da, ” Vasiliev added after the interpreter had translated for him. “Stalin. ” He spoke the Soviet leader’s name like a religious man invoking the Deity-or perhaps a powerful demon.

Kurt Chill said, “Enjoy the responsibility, my o-pop.ru English friends. ” He sent Bagnall and Jones a stiff-armed salute, then strode out of the meeting chamber in the Krom.

Bagnall felt the responsibility, too, as if the air had suddenly turned hard and heavy above his shoulders. He said, “Ken won’t be pleased with us for getting him into this when he wasn’t even at the meeting. ”

“That’s what he gets for not coming, ” Jones replied.

“Mm-maybe so. ” Bagnall looked sidelong at the radarman. “Do you suppose the Germans will want you to give up the fair Tatiana, so as to have no reason to be biased toward the Soviet side? ”

“They’d better not, ” Jones said, “or I’ll bloody well have reason to be biased against them. The one good thing in this whole pestilential town-if anyone tries separating me from her, he’ll have a row on his hands, that I tell you. ”

“What? ” Bagnall raised an eyebrow. “You’re not enamored of spring in Pskov? You spoke so glowingly of it, I recall, when we were flying here in the Lanc. ”

“Bugger spring in Pskov, too, ” Jones retorted, and stomped off.

In fact, spring in Pskov was pretty enough. The Velikaya River, ice-free at last, boomed over the rapids as it neared Lake Pskov. Gray boulders, tinted with pink, stood out on steep hillsides against the dark green of the all-surrounding woods. Grass grew tall on the streets of deserted villages around the city.

The sky was a deep, luminous blue, with only a few puffy little white clouds slowly drifting across it from west to east Along with those clouds, Bagnall saw three parallel lines of white, as straight as if drawn with a ruler. Condensation trails from Lizard jets, he thought, and his delight in the beauty of the day vanished. The Lizards might not be moving yet, but they were watching.

Mordechai Anielewicz looked up from the beet field at the sound of jet engines. Off to the north he saw three small silvery darts heading west. They’ll be landing at Warsaw, he thought with the automatic accuracy of one who’d been spotting Lizard planes for as long as there had been Lizard planes to spot-and German planes before that. Wonder what they’ve been up to.

Whoever headed the Jewish fighters these days would have someone at the airport fluent enough at the Lizards’ speech to answer that for him. So would General Bor-Komorowski of the Polish Home Army. Anielewicz missed getting information like that, being connected to a wider world. He hadn’t realized his horizons would contract so dramatically when he left Warsaw for Leczna.

Contract they had. The town had had several radios, but without electricity, what good were they? Poland’s big cities had electricity, but nobody’d bothered repairing the lines out to all the country towns. Leczna probably hadn’t had electricity at all until after the First World War. Now that it was gone again, people just did without.

Anielewicz went back to work. He pulled out a weed, made sure he had the whole root, then moved ahead about half a meter and did it again. An odd task he thought: mindless and exacting at the same time. You wondered where the hours had gone when you knocked off at the end of the day.

A couple of rows over, a Pole looked up from his weeding and said, “Hey you, Jew! What does the creature that says he’s governor of Warsaw call himself again? ”

The fellow spoke quite without malice, using Anielewicz’s religion to identify him not particularly to scorn him. That he might feel scorned anyhow never entered the Pole’s mind. Because he knew that, Anielewicz didn’t feel scorned, or at least not badly. “Zolraag, ” he answered, carefully pronouncing the two distinct a sounds.

“Zolraag, ” the Pole echoed, less clearly. He took off his cap, scratched his head. “Is he as little as all the others like him? It hardly seems natural. ”

Расскажи о сайте: