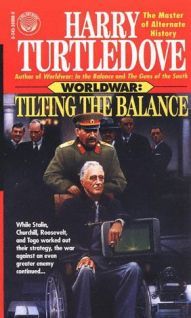

Tilting the Balance

Часть 9

“What if the baby is early? ” Liu Han said.

The little devil’s eyes both swung toward her. “This can happen? ”

“Of course it can, ” Liu Han said. But nothing was of course for the little scaly devils, not when they knew so little about how mankind-and, evidently, womankind-functioned. Then, suddenly, Liu Han had an idea that felt so brilliant, she hugged herself in delight. “Superior sir, would you let me go back down to my own people so a midwife could help me deliver the baby? ”

“This had not been thought of. ” Nossat made a distressed hissing noise. “I see, though, from where you stand, it may have merit. You are not the only female specimen on this ship who will have young born. We will-how do you say? — consider. Yes. We will consider. ”

“Thank you very much, superior sir. ” Liu Han looked down at the floor, as she had seen the scaly devils do when they meant to show respect. Hope sprang up in her like rice plants in spring.

“Or maybe, ” Nossat said, “maybe we bring up a-what word did you use? — a midwife, yes, maybe we bring up a midwife to this ship to help you here. We will consider that, too. You go now. ”

The guards took Liu Han out of the psychologist’s office, led her back to her cell. She felt heavier with each step up the curiously curving stairway that returned her to her deck-and also because the hope which had sprouted now began to wilt.

But it didn’t quite die. The little scaly devils hadn’t said no.

A blank-faced Nipponese guard shoved a bowl of rice between the bars of Teerts’ cell. Teerts bowed to show he was grateful. Feeding prisoners at all was, in Nipponese eyes, a mercy: a proper warrior would die fighting rather than let himself be captured. The Nipponese were in any case sticklers for their own forms of courtesy. Anyone who flouted them was apt to be beaten-or worse.

Since the Nipponese shot down his killercraft, Teerts had had enough beatings-and worse-that he never wanted another (which didn’t mean he wouldn’t get one). But he hated rice. Not only was it the food of his captivity, it wasn’t something any male of the Race would eat by choice. He wanted meat, and could not remember the last time he’d tasted it. This bland, glutinous vegetable matter kept him alive, although he often wished it wouldn’t.

No, that was a falsehood. If he’d wanted to die, he had only to starve himself to death. He did not think the Nipponese would force him to eat; if anything, he might gain their respect by perishing this way. That he cared whether these barbarous Big Uglies respected him showed how low he had sunk.

He lacked the nerve to put an end to himself, though; the Race did not commonly use suicide as a way out of trouble. And so, miserably, he ate, half wishing he never saw another grain of rice, half wishing his bowl held more.

He finished just before the guard came back and took away the bowl. He bowed again in gratitude for that service, though the guard would also have taken it even if he hadn’t finished.

After the guard left, Teerts resigned himself to another indefinitely long stretch of tedium. So far as he knew he was the only prisoner of the Race the Nipponese held here at Nagasaki. No cells within speaking distance of him held even Big Ugly prisoners, lest he somehow form a conspiracy with them and escape. He let his mouth fall open in bitter laughter at the likelihood of that.

Six-legged Tosevite pests scuttled across the concrete floor. Teerts let his eye turrets follow the creatures. He had nothing in particular against them. The real pests on Tosev 3 were the ones who walked upright.

He drilled away into a fantasy where his killercraft’s turbofans hadn’t tried to breathe bullets instead of air. He could have been back at a comfortably heated barracks talking with his comrades or watching the screen or piping music through a button taped to a hearing diaphragm. He could have been snapping bites off a chunk of dripping meat. He could have been in his killercraft again, helping to bring the pestilential Big Uglies under the Race’s control.

Though he heard footsteps coming down the corridor toward him, he did not swing his eyes to see who was approaching. That would have returned him to grim reality too abruptly to bear.

But then the maker of those footsteps stopped outside his cell. Teerts quickly put fantasy aside, like a male saving a computer document so he can attend to something more urgent. His bow was deeper than the one he’d given the guard who fed him. “Konichiwa, Major Okamoto, ” he said in the Nipponese he was slowly acquiring.

“Good day to you as well, ” Okamoto answered in the language of the Race. He was more fluent in it than Teerts was in Nipponese. Learning a new tongue did not come naturally to males of the Race; the Empire had had but one for untold thousands of years. But Tosev 3 was a mosaic of dozens, maybe hundreds, of languages. Picking up one more was nothing out of the ordinary for a Big Ugly. Okamoto had been Teerts’ interpreter and interrogator ever since he was captured.

The Tosevite glanced down the hall. Teerts heard jingling keys as a warder drew near. Another round of questions, then, the pilot thought. He bowed to the warder to show he was grateful for the boon of leaving the cell. Actually he wasn’t as long as he stayed in here, no one hurt him. But the forms had to be observed.

A soldier with a rifle tramped right behind the warder. He covered Teerts as the other male used the key. Okamoto also drew his pistol and held it on Teerts. The pilot would have laughed, except it wasn’t really funny. He only wished he were as dangerous as the Big Uglies thought he was.

The interrogation room was on an upper floor of the prison. Teerts had seen next to nothing of Nagasaki. He knew it lay by the sea; he’d come here by ship after being evacuated from the mainland when Harbin fell to the Race. He didn’t miss seeing the sea. After that nightmare voyage of storms and sickness, he hoped he’d never see-much less ride upon-another overgrown Tosevite ocean again.

“And next time, with luck, he’ll…

“We have decided to produce…

“I know. ” She shook her head. “That’s God’s truth,…

The next gambler paid Liu Han and let…

“Please do, ” Nejas said, Skoob echoing him…

He got back to his own side of…

“Don’t throw like a girl, ” he told Lo;…

Firing broke out off to the south, at…

That triumph faded as he went out onto…

The guard opened the door.…

“Out of Rochester, or maybe Buffalo, ”…

But the collision never came. At…

Ludmila knew each of them…

Musingly, Barbara went on, “I suppose that’s…

“The hall we are using as a barracks…

Churchill said, “I shan’t…

“Oh, indeed. But he’d already figured…

Расскажи о сайте: