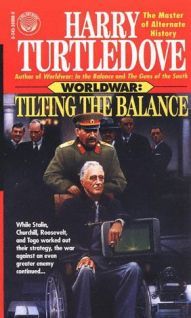

Tilting the Balance

Часть 6

Russie started peeling off dark blue twenty-mark notes and blue-green tens, each printed with a Star of David in the upper left-hand corner and a cross-hatching of background lines that spiderwebbed the bills with more Magen Davids. Each note bore Rumkowski’s signature, which gave the money its sardonic nickname.

The potato seller made his own count after Moishe gave him the bills. Even though it came out right, he still looked unhappy. “Next time you come, bring real money, ” he advised. “I don’t think we’re going to take Rumkies a whole lot longer. ”

“But-” Russie waved to the ubiquitous portraits of the Jewish Eldest.

“He can do what he wants in here, ” the potato seller said. “But he can’t make anybody outside think Rumkies are good for anything but wiping your behind. ” The merchant’s shrug was eloquent.

Russie started back to his flat with the potatoes. It was on the corner of Zgierska and Lekarska, just a couple of blocks from the barbed wire that had sealed off the ghetto of Lodz-Litzmannstad, the Nazis had renamed it when they annexed western Poland to the Reich-from the rest of the city.

Much of the barbed wire remained in place, though paths had been cut through it here and there. In Warsaw, Lizard bombs had knocked down the wall the Germans made. Of course, that barrier had looked like a fortification and most of this one didn’t. But something else went on here, too. The potato seller had said that Rumkowski could do what he wanted inside the ghetto. He’d meant it scornfully, but Moishe thought his words held a truth he hadn’t intended. He had the feeling Rumkowski liked being a big fish, no matter how small his pond was.

At least there were enough potatoes to go around these days. The Lodz ghetto had been as hungry as Warsaw’s, maybe hungrier. The Jews inside remained gaunt and ragged, especially compared to the Poles and http://socialsciences.ru Germans who made up the rest of the townsfolk. They weren’t actively starving any more, though. From where they’d been a year before, that wasn’t just progress. It felt like a miracle.

A horse-drawn wagon clattered up behind Russie. He stepped aside to let it pass. It was piled high with curious-looking objects woven out of straw. “What are those things, anyway? ” Russie called to the driver.

“You must be new in town. ” The fellow pulled back on the reins, slowed his team to an amble so he could talk for a while. “They’re boots, so the Lizards won’t freeze their little chicken feet every time they go out in the snow. ”

“Chicken feet-I like that, ” Russie said.

The driver grinned. “Every time I see two or three Lizards together, I think of the front window of a butcher’s shop. I want to go down the street yelling, ‘Soup! Get your soup fixings here! ’ ” He sobered. “We were making straw boots for the Nazis before the Lizards came. All we had to do was make ’em smaller and change the shape. ”

“Wouldn’t it be fine to make what we wanted just for ourselves, not for one set of masters or another? ” Russie said wistfully. His hands remembered the motions they’d made sewing seams on field-gray trousers.

“Fine, yes. Should you hold your breath? No. ” The drive coughed wetly. Tuberculosis, said the medical student Russie had once been. The driver went on, “It’ll probably happen about the time the Messiah comes. These days, stranger, I’ll take small things-my wife’s not embroidering little eagles for Luftwaffe men, a kholereye on them, to wear on their shoulders. You ask me, that’s fine. ”

“It is fine, ” Russie agreed. “But it shouldn’t be enough. ”

“If God had asked me when He was making the world, I’m sure I could have done much better for His people. Unfortunately, He seems to have been otherwise engaged. ” Coughing again, the driver flicked the reins and sent the wagon rattling on down the street. Now at least he could go outside the ghetto.

More posters of Rumkowski were plastered on the front of Russie’s block of flats. Under his lined face was one word-WORK-in Yiddish, Polish, and German. His hope had been to make the industrious Jews of Lodz so valuable to the Nazis that they would not want to ship them to extermination camps. It hadn’t worked; the Germans were running trains to Chelmno and other camps until the day the Lizards drove them away. Russie wondered how much Rumkowski had known about that.

He also wondered why Rumkowski fawned so on the Lizards when only horror had come from his efforts at accommodating the Nazis. Maybe he didn’t want to lose the shadowy power he enjoyed as Jewish Eldest. Or maybe he just didn’t know any other way to deal with overlords so much mightier than he. For the Eldest’s sake, Russie hoped the latter was true.

Shlepping the potatoes up three flights of stairs as he walked down the hallway to his flat, years of bad nutrition and weeks of being cooped up inside the cramped bunker had taken their toll on his wind and on his strength generally. He tried the door. It was locked. He rapped on it. Rivka let him in.

A small tornado in a cloth cap tackled him just above the knees. “Father, Father! ” Reuven squealed. “You’re back! ” Ever since they’d come out of the bunker-where they’d been together every moment, awake and asleep-Reuven had been nervous about his going away for any reason. He was, however, starting to get over that, for he asked, “Did you bring me anything? ”

“Sorry, son; not this time. I just went out for food, ” Moishe said. Reuven groaned in disappointment. His father pulled his cap down over his eyes. He thought that was funny enough to make up for the lack of trinkets.

People sold toys in the market square. How many of them, though, used to belong to children who’d died in the ghetto or been taken away to Chelmno or some other camp? When even something that should have been joyous, like buying a toy, saddened and frightened you because you wondered why it was for sale, you began to feel in your belly what the Nazis had done to the Jews of Poland.

Rivka took the sack of potatoes. “What did you have to pay? ” she asked.

“Four hundred and fifty Rumkies, ” he answered.

She stopped in dismay. “This is only ten kilos, right? Last week ten kilos only cost me 320. Didn’t you haggle? ” When he shook his head, she rolled her eyes toward the heavens. “Men! See if I let you go shopping again. ”

“The Rumkie’s worth less every day, ” he said defensively. “In fact, it’s almost worthless, period. ”

As if she were explaining a lesson to Reuven, she said, “Last week, the potato seller’s first price for me was 430 Rumkies. I just laughed at him. You should have done the same. ”

“I suppose so, ” he admitted. “It didn’t seem to matter, not when we have so many Rumkies. ”

Расскажи о сайте: