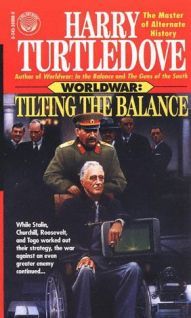

Tilting the Balance

Автор: Harry Turtledove

Издатель: Del Rey 1995

ISBN: 0345389980

Навигация: Tilting the Balance → XIV

Часть 7

“All right by me. ” Anielewicz’s back protested when he stood up straight. If aches bothered the Pole, he didn’t show it. He’d worked on a farm all his life, not just for a couple of weeks.

Leczna was an ordinary Polish town, bigger than a village, not nearly big enough to be called a city. It was small enough for people to know one another, and for Mordechai to stand out as a stranger. People still greeted him in a friendly enough way, Jews and Poles alike. The two groups seemed to get on pretty well-better than in most places in Poland, anyhow.

Maybe the friendly greetings came because he was staying with the Ussishkins. Judah Ussishkin had been doctoring Jews and gentiles alike for more than thirty years; his wife Sarah, a midwife herself, must have delivered half the population of the town. If the Ussishkins vouched for you, you were good as gold in Leczna.

Most of the Jews lived in the southeastern part of town. As was fitting for one who worked with both halves of the populace, Dr. Ussishkin had his house at the edge of the Jewish district. His next-door neighbors on one side, in fact, were Poles. Roman Klopotowski waved to Anielewicz as he came down the street toward the doctor’s house. So did Klopotowski’s daughter Zofia.

Mordechai waved back, which made Zofia’s face light up. She was a pretty blond girl-no, woman; she had to be past twenty. Anielewicz wondered why she hadn’t married. Whatever the reason, she’d plainly set her sights on him.

He didn’t know what to do about that (he knew what he wanted to do, but wasn’t nearly so sure it was a good idea). For the moment, he did nothing but walk up the steps onto the front porch of Dr. Ussishkin’s house and, after wiping his feet, on into the parlor.

“Good evening, my guest, ” Judah Ussishkin said with a dip of his head that was almost a bow. He was a broad-shouldered man of about sixty, with a curly gray beard, sharp dark eyes behind steel-rimmed spectacles, and an old-fashioned courtliness that brought with it a whiff of the vanished days of the Russian Empire.

“Good evening, ” Mordechai answered, nodding in return. He’d grown up in a more hurried age, and could not match the doctor’s manners. He might even have resented them had they not been so obviously genuine rather than affectation. “How was your day? ”

“Well enough, thank you for asking, although it would have been better still had I had more medicines with which to work. ”

“We would all be better off if we had more of everything, ” Mordechai said.

The doctor raised a forefinger. “There I must disagree with you, my young friend: of troubles we have more than a sufficiency. ” Anielewicz laughed ruefully and nodded, yielding the point.

Sarah Ussishkin came out of the kitchen and interrupted: “Of potatoes we also have a sufficiency, at least for now. Potato soup is waiting, whenever you tzaddiks decide you’d rather eat than philosophize. ” Her smile belied the scolding tone in her voice. She’d probably been a beauty when she was young; she remained a handsome woman despite gray hair, the beginning of a stoop, and a face that had seen too many sorrows and not enough joys. She moved with a dancer’s grace, making her long black skirt swirl about her at every step.

The potato soup steamed in its pot and in three bowls on the table by the stove. Judah Ussishkin murmured a blessing before he picked up his spoon. Out of politeness to him, Anielewicz waited till he was done, though he’d lost that habit and his stomach was growling like an angry wolf.

The soup was thick not only with grated potatoes but also with chopped onion. Chicken fat added rich flavor and sat in little golden globules on the surface of the soup. Mordechai pointed to them. “I always used to call those ‘eyes’ when I was a little boy. ”

“Did you? ” Sarah laughed. “How funny. Our Aaron and Benjamin said just the same thing. ” The laughter did not last long. One of the Ussishkins’ sons had been a young rabbi in Warsaw, the other a student there. No word had come from them since the Lizards drove out the Nazis and the closed ghetto ended. The odds were mournfully good that meant they were both dead.

Mordechai’s soup bowl emptied with amazing speed. Sarah Ussishkin filled it again, and he emptied it the second time almost as fast as the first. “You have a healthy appetite, ” Judah said approvingly.

“If a man works like a horse, he needs to eat like a horse, too, ” Anielewicz replied. The Germans hadn’t cared about that; they’d worked the Jews like elephants and fed them like ants. But the work they’d got out of the Jews was just a sidelight; they’d been more interested in getting rid of them.

Supper was just ending when someone pounded on the front door. “Sarah, come quick! ” a frightened male voice bawled in Yiddish. “Hannah’s pains are close together. ”

Sarah Ussishkin made a wry face as she got up from her chair. “It could be worse, I suppose, ” she said. “That usually happens in the middle of a meal. ” The pounding and shouting went on. She raised her voice: “Leave us our door in one piece, Isaac. I’m coming. ” The racket stopped. Sarah turned to her husband for a moment “I’ll probably see you tomorrow sometime. ”

“Very likely, ” he agreed. “God forbid you should have to call me sooner, for that could only mean something badly wrong. I have chloroform, a little, but when it is gone, it is gone forever. ”

WELCOME TO CHUGWATER, POPULATION…

“That’s true only to a…

“If I defend the area, I…

“Nezavisna Drzava Hrvatska-the…

Mutt went over to have a look at what Freddie…

“I know. ” She shook her head.…

Bobby Fiore almost wished he was still on…

Clip-clop, clip-clop. Colonel…

He got back to his own side of the bed in…

His Panther backed through the little stream…

There down below-was that a light?…

“The hall we are using as a…

Nevertheless, Molotov owed allegiance…

“They won’t last forever, ” Rivka…

Skorzeny threw back his…

That’s something, anyhow, Jager thought.…

The guard opened the door. Teerts…

Расскажи о сайте: