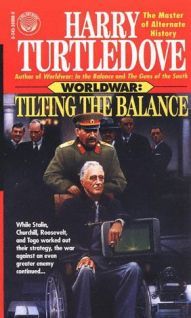

Tilting the Balance

Часть 1

Ludmila Gorbunova did not care for Moscow. She was from Kiev, and thought the Soviet capital drab and dull. Her impression of it was not improved by the endless grilling she’d had from the NKVD. She’d never imagined the mere sight of green collar tabs could reduce her to fearful incoherence, but it did.

And, she knew, things could have been worse. The chekists were treating her with kid gloves because she’d flown Comrade Molotov, second in the Soviet Union only to the Great Stalin, and a man who loathed flying, to Germany and brought him home in one piece. Besides, the rodina-the motherland-needed combat pilots. She’d stayed alive through most of a year against the Nazis and several months against the Lizards. That should have given her value above and beyond what she got for ferrying Molotov around.

Whether it did, however, remained to be seen. A lot of very able, seemingly very valuable people had disappeared over the past few years, denounced as wreckers or traitors to the Soviet Union or sometimes just vanished with no explanation at all, as if they had suddenly ceased to exist…

The door to the cramped little room (cramped, yes, but infinitely preferable to a cell in the Lefortovo prison) in which she sat came open. The NKVD man who came in wore three crimson oblongs on his collar tabs. Ludmila bounced to her feet. “Comrade Lieutenant-Colonel! ” she said, saluting.

He returned the salute, the first time that had happened since the NKVD started in on her. “Comrade Senior Lieutenant, ” he acknowledged. “I am Boris Lidov. ” She blinked in surprise; none of her questioners had bothered giving his name till now, either. Lidov looked more like a schoolmaster than an NKVD man, not that that meant anything. But he surprised her again, saying, “Would you like some tea? ”

“Yes, thank you very much, Comrade Lieutenant-Colonel, ” she answered-quickly, before he changed his mind. The German attack had deranged the Soviet distribution system, that of the Lizards all but destroyed it. These days, tea was rare and precious.

Well, she thought, the NKVD will have it if anyone does. And sure enough, Lidov stuck his head out the door and bawled a request. Within moments, someone fetched him a tray with two gently steaming glasses. He took it, set it on the table in front of Ludmila. “Help yourself, ” he, said. “Choose whichever you wish; neither one is drugged, I assure you. ”

He didn’t need to assure her; that he did so made her suspicious again. But she took a glass and drank. Her tongue found nothing in it but tea and sugar. She sipped again, savoring the taste and the warmth. “Thank you, Comrade Lieutenant-Colonel. It’s very good, ” she said.

Lidov made an indolent gesture, as If to say she didn’t need to thank him for anything so small. Then he said idly, as if making casual conversation, “You know, I met your Major Jager-no, you’ve said he’s Colonel Jager now, correct? — your Colonel Jager, I should say, after you brought him here to Moscow last summer. ”

“Ah, ” Ludmila said, that being the most noncommittal noise she could come up with. She decided it was not enough.

“Comrade Lieutenant-Colonel, as I have said before, he is not my colonel by any means. ”

“I do not necessarily condemn, ” Lidov said, steepling his fingers. “The ideology of the fascist state is corrupt, not the German people. And”-he coughed dryly-“the coming of the Lizards has shown that progressive economic systems, capitalist and socialist alike, must band together lest we all fall under the oppression of the ancient system wherein the relationship is slave to master, not worker to boss. ”

“Yes, ” Ludmila said eagerly. The last thing she wanted to do was argue about the dialectic of history with an NKVD man, especially when his interpretation seemed to her advantage.

Lidov went on, “Further, your Colonel Jager helped perform a service for the people of the Soviet Union, as he may have mentioned to you. ”

“No, I’m afraid he didn’t. I’m sorry, Comrade Lieutenant-Colonel, but we talked very little about the war when we saw each other in Germany. We-” Ludmila felt her face heat. She knew what Lidov had to be thinking. Unfortunately-from her point of view-he was right.

He looked down his long, straight nose at her. “You like Germans well, don’t you? ” be said sniffily. “This Jager in Berchtesgaden, and you attached his gunner”-he pulled out a scrap of paper, checked a name on it-“Georg Schultz, da, to the ground crew at your airstrip. ”

“He is a better mechanic than anyone else at the airstrip. Germans understand machinery better than we do, I think. But as far as I am concerned, he is only a mechanic, ” Ludmila insisted.

“He is a German. They are both Germans. ” So much for Lidov’s words about the solidarity of peoples with progressive economic systems. His flat, hard tone made Ludmila think of a trip to Siberia on an unheated cattle car, or of a bullet in the back of the neck. The NKVD man went on, “It is likely that Comrade Molotov will dispense with the services of a pilot who forms such un-Soviet attachments. ”

“I am sorry to hear that, Comrade Lieutenant-Colonel, ” Ludmila said, though she knew Molotov would have been glad to dispense with the services of any pilot, given his attitude about flying. But she insisted, “I have no attachments to Georg Schultz save those of the struggle against the Lizards. ”

“And to Colonel Jager? ” Lidov said with the air of a man calling checkmate. Ludmila did not answer, she knew she was checkmated. The lieutenant-colonel spoke as if pronouncing sentence: “Because of this conduct of yours, you are to be returned to your former duties without promotion. Dismissed, Comrade Senior Lieutenant. ”

Ludmila had been braced for ten years in the gulag and another five of internal exile. She needed a moment to take in what she’d just heard. She jumped to her feet. “I serve the Soviet state, Comrade Lieutenant-Colonel! ” Whether you believe me or not, she added to herself.

His own poster still appeared here and there,…

Somehow, though, she did…

Rivka walked out of the kitchen…

The air-raid siren at Bruntingthorpe…

Atvar read intently for a little while,…

“Still here in Lodz, ” Goldfarb…

Bobby Fiore almost wished he was still on the…

“Please do, ” Nejas said, Skoob…

Chill spoke a single word:…

“Aw, Sarge, they were just struttin’ around,…

He could not fault the logic,…

Back to the wagons. Ullhass…

“I understand this, ” Atvar…

Night was falling when they approached…

“First, I suppose, to confirm what…

Расскажи о сайте: