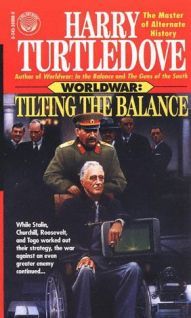

Tilting the Balance

Автор: Harry Turtledove

Издатель: Del Rey 1995

ISBN: 0345389980

Навигация: Tilting the Balance → XIII

Часть 4

He wondered if the Lizards called it something altogether different.

A little more than an hour brought him into the outskirts of Lodz. He’d been told the town had fallen to the Nazis almost undamaged. It wasn’t undamaged now. The briefings he’d read on the submarine said the Germans had put up a hell of a scrap before the Lizards drove them out of town, and that they’d lobbed occasional rockets or flying bombs (the briefings weren’t very clear about which) at it ever since.

Most of the people in the outer part of the city were Poles. If any German settlers remained from Lodz’s brief spell as Litzmannstadt, they were lying low. Sneers from the Poles were bad enough. He didn’t know what he would have done with Germans gaping at him. All at once, he regretted hoping the German bombers had a good mission. Then he got angry at himself for that regret. The Germans might not be much in the way of human beings, but against the Lizards they and England were on the same side.

He walked on down Lagiewnicka Street toward the ghetto. The wall the Nazis had built was still partly intact, although in the street itself it had been knocked down to allow traffic once more. As soon as he set foot on the Jewish side, he decided that while the Germans and England might be on the same side, the Germans and he would never be.

The smell and the crowding hit him twin sledgehammer blows. He’d lived his whole life with plumbing that worked. He’d never reckoned that a mitzvah, a blessing, but it was. The brown reek of sewage (or rather, slops), garbage, and unwashed humanity made him wish he could turn off his nose.

And the crowd! He’d heard men who’d been in India and China talk of ant heaps of people, but he hadn’t understood what that meant The streets were jammed with men, women, children, carts, wagons-a good-sized city was boiled down into a few square blocks, like bouillon made into a cube. People bought, sold, argued, pushed past one another, got in each other’s way, so that block after block of ghetto street felt like the most crowded pub where Goldfarb had ever had a pint.

The people-the Jews-were dirty, skinny, many of them sickly-looking. After tramping down from the Polish coast, Goldfarb was none too clean himself, but whenever he saw someone eyeing him, he feared the flesh on his bones made him conspicuous.

And this misery, he realized, remained after the Nazis were the better part of a year out of Lodz. The Jews now were fed better and treated like human beings. What the ghetto had been like under German rule was-not unimaginable, for he imagined it all too vividly, but horrifying in a way he’d never imagined till now.

“Thank you, Father, for getting out when you did, ” he said. For a couple of blocks he simply let himself be washed along like a fish in a swift-flowing stream. Then he began moving against the current in a direction of his own choosing.

Posters of Mordechai Chaim Rumkowski seemed to follow him wherever he went. Some were tattered and faded, some as new and bright as if they’d been put up yesterday, which they probably had. Rumkowski stared down at Goldfarb from a variety of poses, but always looked stern and commanding.

Goldfarb shook his head; the briefing papers had had considerable to say about Rumkowski and his regime in Lodz, but not much of that was good. In sum, he amounted to a pocket Jewish Hitler. Just what we need, Goldfarb thought.

A couple of times, he passed Order Service men with their armbands and truncheons. He noticed them not only for those, but also because they looked uncommonly well-fed. A pocket Jewish SS, too. Wonderful. Goldfarb kept his head down and did his best to pretend he was invisible.

But he had to look up from time to time to tell where he was going; studying a street map of Lodz didn’t do enough to let him make his way through the town itself. Luckily, being one mote in a swirling crowd kept him from drawing special notice. After three wrong turns-about half as many as he’d expected-he walked into a block of flats on Mostowski Street and started climbing stairs.

He knocked on what he hoped was the right door. A woman a couple of years older than he was-she would have been pretty If she hadn’t been so thin-opened it and stared at his unfamiliar face with fear-widened eyes. “Who are you? ” she demanded.

Goldfarb got the idea something unpleasant would happen to him if he gave the wrong answer. He said, “I’m supposed to tell you even Job didn’t suffer forever. ”

“And I’m supposed to tell you it must have seemed that way to him. ” The woman’s whole body relaxed. “Come in. You must be Moishe’s cousin from England. ”

“That’s right, ” he said. She closed the door behind him. He went on, “And you’re Rivka? Where’s your son? ”

“He’s out playing. In the crowds on the street, the risk is small, and besides, someone has an eye on him. ”

“Good. ” Goldfarb looked around. The flat was tiny, but so bare that it seemed larger. He shook his head in sympathy.

“You must be sick to death of moving. ”

Rivka Russie smiled for the first time, tiredly. “You have no idea. Reuven and I have moved three times since Moishe didn’t come back to the flat we’d just taken. ” She shook her head. “He thought someone had known who he was. We must have been just too late getting out of the other place. If it hadn’t been for the underground, I don’t know what we would have done. Got caught, I suppose. ”

“They got word to England, too, ” Goldfarb said, “and orders eventually got to me. ” He wondered if they would have, had Churchill not spent a while talking with him at Bruntingthorpe. “I’m supposed to help get Moishe out of here and take him-and you and the boy back to England with me. If I can. ”

“Can you do that? ” Rivka asked eagerly.

“Gott vayss-God knows, ” he said. That won a startled laugh from her. He went on, “I’m no commando or hero or anything like that. I’ll work with your people and I’ll do the best I can, that’s all. ”

“A better answer than I expected. ” Her voice was judicious.

“Is he still in Lodz? ” Goldfarb asked. “That’s the last information I had, but it’s not necessarily good any more. ”

“As far as we know, yes. The Lizards aren’t in a lot of hurry about dealing with him. That doesn’t make sense to me, when he did such a good job of embarrassing them. ”

“They’re more sure than quick, ” Goldfarb said, remembering pages from the briefing book. “Very methodical, but not swift. What sort of charge do they have him up on? ”

“Disobedience, ” Rivka said. “From everything he ever said while he was on better terms with them, they couldn’t accuse him of anything much worse. ”

That fit in with what Goldfarb had read, too. The Lizards seemed rank-, class-, and duty-conscious to a degree that made the English and even the Japanese look like wild-eyed, bomb-throwing anarchists. In that kind of society, disobedience had to be as heinous a sin as blasphemy in the Middle Ages.

With a flourish, he handed the glass to…

But no one hung hack or hesitated. Better…

“The hall we are using as…

The newsreel ended with a burst…

He’d intended that for sarcasm.…

The next gambler paid Liu Han and let fly. Wham!…

He hadn’t expected that to…

Ludmila knew each of…

The junior officers all towered over Hipple,…

“Don’t throw like a girl,…

Russie started peeling off dark blue twenty-mark…

All three males were luxuriating in…

His own poster still appeared…

Somehow, though, she did not…

Daniels paused in his cleaning…

Rivka walked out of the kitchen to…

Расскажи о сайте: