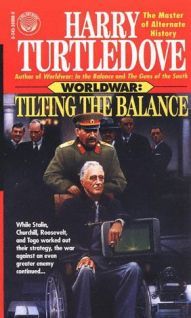

Tilting the Balance

Автор: Harry Turtledove

Издатель: Del Rey 1995

ISBN: 0345389980

Навигация: Tilting the Balance → XVI

Часть 1

Moishe Russie paced back and forth in his cell. It could have been worse; he could have been in a Nazi prison. They would have had special fun with him because he was a Jew. To the Lizards, he was just another prisoner, to be kept on ice like a bream until they figured out exactly what they wanted to do with him-or to him.

He supposed he should thank God they weren’t often in a hurry. They’d interrogated him after he was caught. On the whole, he’d spoken freely. He didn’t know many names, so he couldn’t incriminate most of the people who’d helped him-and he figured they were smart enough not to stay in any one place too long, either.

The Lizards hadn’t bothered questioning him lately. They just held him, fed him (at least as much as he’d been eating while he was free), and left him to fight boredom as best he could. They didn’t put prisoners in the cells to either side of his or across from it Even if they had, neither the Lizard guards nor their Polish and Jewish flunkies allowed much chatter.

The Lizard guards ignored him as long as he didn’t cause trouble. The Poles and Jews who served them still thought he was a child molester and a murderer. “I hope they cut your balls off one at a time before they hang you, ” a Pole said. He’d given up answering back. They didn’t believe him, anyhow.

Some blankets, a bucket of water and a tin cup, another bucket for slops-such were his worldly goods. He wished he had a book. He didn’t care what it was; he would have devoured a manual on procedures for inspecting light bulbs. As things were, he stood, he sat, he paced, he yawned. He yawned a lot.

A Polish guard stopped in front of the cell. He shifted the club he carried from right hand to left so he could take a key out of his pocket. “On your feet, you, ” he growled. “They got more questions for you, or maybe they’re just gonna chop you up to see how you got to be the kind of filthy thing you are. ”

As Russie got up, he remembered there were worse things than boredom. Interrogation was one of them, not so much for what the Lizards did as for the never-ending terror of what they might do.

Crash! Something hit the side of the prison like a bomb. At first, as he staggered and clapped hands to ears, Moishe thought that was just what it was, that the Germans had landed one of their rockets right in the middle of Lodz.

Then another crash came, hard on the heels of the first. It flung the Pole headlong against the bars of Russie’s cell. The guard went down, stunned and bleeding from the nose. The key flew from his hand. In a spy story, Moishe thought, it would have had the consideration to land in his cell so he could grab it and escape. Instead, it bounced down the hall, impossibly far out of reach.

Still another crash-this one knocked Russie off his feet and showed daylight through a hole in the far wall. As he curled up into a frightened ball, he wondered what the devil was going on. The Nazis couldn’t have fired three rocket bombs so fast… could they? Or was it artillery? How could they have brought artillery through Lizard held territory to shell Lodz?

His ears rang, but not so much that he couldn’t hear the nasty chatter of gunfire. A Lizard ran down the hall, carrying one of his kind’s wicked little automatic rifles. He fired out through, the hole the shells had made in the wall. Whoever was outside returned fire. The Lizard reeled back, red, red blood spurting from several wounds.

Someone-a human-burst in through the hole. Another Lizard came running up. The man cut him down; he had a submachine gun that at close range was as lethal, as anything the aliens used. More men rushed in behind the first. One of them shouted, “Russie! ”

“Here! ” Moishe yelled. He uncoiled and scrambled to his feet, hope suddenly overpowering fright.

The fellow who’d called his name spoke in oddly accented Yiddish: “Stand back, cousin. I’m going to blow the lock off your door. ”

Spy stories came in handy after all. Russie pointed to the floor of the corridor. “No need. There’s the key. This mamzer”-he pointed to the unconscious Pole-“was about to take me away for more questions. ”

“Oy. Wouldn’t that have been a balls-up? ” The last wasn’t in Yiddish; Moishe wasn’t sure what language it was in. He had precious little time to wonder, the man grabbed the key, turned it in the lock. He yanked the door open. “Come on. Let’s get out of here. ”

Moishe needed no further urging. Alarms were clanging somewhere, off in the distance; power here seemed to be out. As he ran toward the hole in the outer wall, he asked, “Who are you, anyway? ”

“I’m a cousin of yours from England. David Goldfarb’s my name. Now cut the talk, will you? ”

Moishe obediently cut the talk. Bullets started flying again; he ran even harder than he had before. Behind him, somebody screamed. The medical student part of him wanted to go back and help. The rest made him keep running-out through the hole, out through the open space around the prison, out through a gap in the razor wire, out through the screaming, gaping people in the street.

“There are machine guns on the roof, ” he gasped. “Why aren’t they shooting at us? ”

“Snipers, ” his cousin answered. “Good ones. Shut up. Keep running. We aren’t out of this mess yet. ”

Russie kept running. Then, abruptly, his companions, those who survived, threw away their weapons as they rounded a corner. When they rounded another corner, they stopped running. David Goldfarb grinned. “Now we’re just ordinary people-you see? ”

“I see, ” Moishe answered-and, once it was pointed out to him, he did.

“It won’t last, ” said one of the gunmen who’d been with Goldfarb. “They’ll turn this town inside out looking for us. Somebody kills a Lizard, they get nasty about that. ” His teeth showed white through tangled brown beard.

“Which means it’s a good idea to get away from the net before they go fishing, ” Goldfarb said. “Cousin Moishe, we’re going to take you back to England. ”

“Without Rivka and Reuven, I won’t go. ” As soon as the words were out of his mouth, Russie realized how selfish and boorish they sounded. These men had risked their lives to save him; their comrades had died. Who was he to set conditions on what they did? But he didn’t apologize, because however selfish what he’d said sounded, he also realized he’d meant it.

“Assembled shiplords, I…

Mutt looked down at Donlan. The kid’s…

Skorzeny threw back his head…

The air-raid siren at Bruntingthorpe…

Even before his conscious mind willed…

“Out of Rochester, or maybe Buffalo,…

Vernon, however, kept right on talking, so Jens…

“I understand this, ” Atvar said. “What…

His Panther backed through the little…

Heinrich Jager gave his interrogator a dirty…

Those trees also concealed Tosevites,…

That triumph faded as he went out…

“Prepare yourself for immediate departure for…

“Aw, Sarge, they were just struttin’…

With a flourish, he handed the glass…

Ludmila nodded. Strange, she thought,…

Russie started peeling off dark…

Расскажи о сайте: