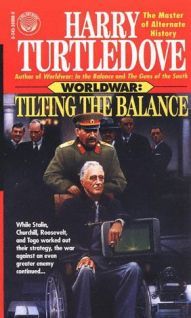

Tilting the Balance

Автор: Harry Turtledove

Издатель: Del Rey 1995

ISBN: 0345389980

Навигация: Tilting the Balance → XIX

Часть 2

“I think that went very well, ” Jacobi said. “With any luck at all, it should leave the Lizards quite nicely browned off. ”

“I hope so, ” Moishe said. He got up and stretched. Wireless broadcasting was not physically demanding, but it left him worn all the same. Getting out of the studio always came as a relief.

Jacobi held the door open for him. They went out together. Waiting in the hallway stood a tall, thin, tweedy Englishman with a long, craggy face and dark hair combed high in a pompadour. He nodded to Jacobi. They spoke together in English. Jacobi turned to Moishe and switched to Yiddish: “I’d like to introduce you to Eric Blair. He’s talks producer of the Indian Section, and he goes in after us. ”

Russie stuck out his hand and said, “Tell him I’m pleased to meet him. ”

Blair shook hands with him, then spoke in English again. Jacobi translated: “He says he’s even more pleased to meet you: you’ve escaped from two different sets of tyrants, and honestly described the evils of both. ” He added, “Blair is a very fine fellow, hates tyrants of all stripes. He fought against the fascists in Spain-almost got killed there-but he couldn’t stomach what the Communists were doing on the Republican side. An honest man. ”

“We need more honest men, ” Moishe said.

Jacobi translated that for Blair. The Englishman smiled, but suffered a coughing fit before he could answer. Moishe had heard those wet coughs in Warsaw more times than he cared to remember. Tuberculosis, the medical student in him said. Blair mastered the coughs, then spoke apologetically to Jacobi.

“He says he’s glad he did that out here rather than in the studio while he was recording, ” Jacobi said. Moishe nodded; he understood and admired the workmanlike, professional attitude. You worked as hard as you could for as long as you could, and if, you fell in the traces you had to hope someone else would carry on.

Blair pulled his script from a waistcoat pocket and went into the studio. Jacobi said, “I’ll see you later, Moishe. I’m afraid I have a mountain of forms to fill out. Perhaps we should put up stacks of paper in place of barrage balloons. They’d be rather better at keeping the Lizards away, I think. ”

He headed away to his upstairs office. Moishe went outside. He decided not to head back to his flat right away, but walked west down Oxford Street toward Hyde Park. People mostly women, often with small children in tow-bustled in and out of Selfridge’s. He’d been in the great department store once or twice himself. Even with wartime shortages, it held more goods and more different kinds of goods than were likely to be left in all of Poland. He wondered if the British knew how lucky they were.

The great marble arch where Oxford Street, Park Lane, and Bayswater Road came together marked the northeast corner of Hyde Park. Across Park Lane from the arch was the Speakers’ Corner where men and women climbed up on crates or chairs or whatever they had handy and harangued whoever would hear. He tried to imagine such a thing in Warsaw, whether under Poles, Nazis, or Lizards. The only thing he could picture was the public executions that would follow unbridled public speech. Maybe. England had earned its luck after all.

Only a handful of people listened to-or heckled-the speakers. The rest of the park was almost as crowded with people tending their gardens. Every bit of open space in London grew potatoes, wheat, maize, beets, beans, peas, cabbages. German submarines had put Britain under siege; the coming of the Lizards brought little relief. They weren’t as hard on shipping, but America and the rest of the world, had less to send these days.

The island wasn’t having an easy time trying to feed itself. Perhaps in the long run it couldn’t not if it wanted to keep on turning out war goods, too. But if the English knew they were beaten, they didn’t let on.

All through the park, trenches, some bare, some with corrugated tin roofs were scattered among the garden plots. Like Warsaw, London had learned the value of air raid shelters no matter how makeshift. Moishe had dived into one of them himself when the sirens began to wail a few days before. The old woman sprawled in the dirt a few feet away had nodded politely as if they were meeting over tea. They d stayed in there till the all clear sounded, then dusted themselves off and gone on about their business.

Moishe turned and retraced his steps down Oxford Street. He explored with caution; wandering a couple of blocks away from the streets he’d already learned had got him lost more than once. And he was always looking the wrong way, forgetting traffic moved on the left side of the street, not the right. Had more motorcars been on the road, he probably would have been hit by now.

He turned right onto Regent Street, then left onto Beak. A group of men was going into a restaurant there-the Barcelona, he saw as he drew closer. He recognized the tall, thin figure of Eric Blair in the party; the India Section man must have finished his talk and headed off for lunch.

Beak Street led Russie to Lexington and from it to Broadwick Street, on which sat his block of flats. As with much of the Soho district, it held more foreigners than Englishmen: Spaniards, Indians, Chinese, Greeks-and now a family of ghetto Jews.

He turned the key in the lock, opened the door. The rich odor of cooking soup greeted him like a friend from home. He shrugged out of his jacket; the electric fire here kept the flat comfortably warm. Not sleeping under mounds of blankets and overcoats was another reward of coming to England.

Mutt Daniels crouched in a foxhole…

Skorzeny threw back his head and bellowed…

He hadn’t expected that to mean…

Firing broke out off to the south, at first…

“We have decided to produce both…

He said, “General Chill…

He knew about shakedowns.…

“I understand this, ” Atvar said.…

Ludmila knew each of them wanted…

“I wish we were in Denver, ” Barbara…

Somehow, though, she did not…

“Out of Rochester, or maybe Buffalo,…

The air-raid siren at Bruntingthorpe began…

“On that, if you’reverse…

Churchill said, “I shan’t forget this…

“Please, superior sir, ” Liu…

Night was falling when they…

Расскажи о сайте: