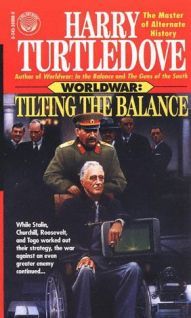

Tilting the Balance

Автор: Harry Turtledove

Издатель: Del Rey 1995

ISBN: 0345389980

Навигация: Tilting the Balance → III

Часть 8

“This if you do: unless you let me send a letter-just an ordinary, handwritten letter-to Barbara, you get no more work out of me, and that’s that. ”

“Too risky, ” Hexham said. “Suppose our courier is captured-”

“Suppose he is? ” Jens retorted. “I’m not going to write about uranium, for God’s sake. I’m going to let her know I’m alive and in one piece and that I love her and I miss her. That’s all. I won’t even sign my last name. ”

“No, ” said Hexham.

“No, ” said Larssen. They glared at each other. The toothpick twitched.

Oscar escorted Larssen back to BOQ. He lay down on his cot. He was ready to wait as long as it took.

The fat man in the black Stetson paused in the ceremony first to spit a brown stream into the polished brass spittoon near his feet (not a drop clung to his handlebar mustache) and then to sneak another glance at the Lizards who stood in one corner of his crowded office. He half shrugged and resumed: “By the authority vested in me as justice of the peace of Chugwater, Wyoming, I now pronounce you man and wife. Kiss her, boy. ”

Sam Yeager tilted Barbara Larssen’s-Barbara Yeager’s-face up to his. The kiss was not the decorous one first post-wedding kisses are supposed to be. She molded herself against him. He squeezed her tight.

Everybody cheered. Enrico Fermi, who was serving as best man, slapped Yeager on the back. His wife Laura stood on tiptoe to kiss Sam’s cheek. Seeing that, the physicist made a Latin production out of kissing Barbara on the cheek. Everybody cheered again, louder than ever.

Just for a second, Yeager’s eyes went to Ullhass and Ristin. He wondered what they made of the ceremony. From what they said, they didn’t mate permanently-and to them, human beings were barbarous aliens.

Well, to hell with what they think of human beings, he thought. As far as he was concerned, having Fermi as his best man was almost-not quite-as exciting as getting married to Barbara. He’d been married once before, unsuccessfully, and he’d sometimes thought about marrying again. But never in all the hours he’d spent reading science fiction on trains and buses between one minor-league game and the next had he thought he’d really get to hobnob with scientists. And having a Nobel Prize winner as your best man was about as hob a nob as you could find.

The justice of the peace-the sign on his door said he was Joshua Sumner, but he seemed to go by Hoot-reached into a drawer of the fancy old rolltop desk that adorned his office. What he pulled out was most unjudicial: a couple of shot glasses and a bottle about half full of dark amber fluid.

“Don’t have as much here as we used to. Don’t have as much here as we’d like, ” he said as he poured each glass full. “But we’ve still got enough for the groom to make a toast and the bride to drink it. ”

Barbara eyed the full shot dubiously. “If I drink all that, I’ll just go to sleep. ”

“I doubt it, ” the justice of the peace said, which raised more whoops from the predominantly male crowd in his office. Barbara turned pink and shook her head in embarrassment but took the glass.

Yeager took his, too, careful not to spill a drop. He knew what he was going to say. Even though he hadn’t expected to have to propose a toast, one leaped into his mind the moment Sumner said he’d need it. That didn’t usually happen with him; more often than not, he’d come up with snappy comebacks a week too late to use them.

Not this time, though. He raised the shot glass, waited for quiet. When he got it, he said, “Life goes on, ” and knocked back the shot. The whiskey burned its way down his throat, filled his middle with warmth.

“Oh, that’s good, Sam, ” Barbara said softly. “That’s just right. ” She lifted the shot glass to her lips. She started to sip, but at the last moment drank it all down at once as Sam had. Her eyes opened very wide and started to water. She turned much redder than she had when the justice of the peace flustered her. What should have been her next breath became a sharp cough instead. People laughed and clapped anyhow.

Joshua Sumner said, “Don’t do that every day, you tell me? ” He had the deadpan drollness that goes with many large men who are sparing of speech.

As the wedding party filed out of the justice of the peace’s office, Ristin said, “What you do here, Sam, you, and Barbara? You make”-he spoke a couple of hissing words in his own language-“to mate all the time? ”

“An agreement that would be in English, ” Yeager said. He squeezed Barbara’s hand. “That’s just what we did, even if I am too old to mate ‘all the time. ’ ”

“Don’t confuse him, ” Barbara said with a cluck in her voice.

They went outside Chugwater was about fifty miles north of Cheyenne. Off against the western horizon, snow-cloaked mountains loomed. The town itself was a few houses, a general store and the post office that also housed the sheriff’s office and that of the justice of the peace. Hoot Sumner was also postmaster and sheriff, and probably none too busy even if he did wear three hats.

The sheriff’s office (fortunately, from Yeager’s point of view) boasted a single jail cell big enough to hold the two Lizard POWs. That meant he and Barbara got to spend their wedding night without Ristin and Ullhass in the next room. Not that the Lizards were likely to pick that particular night to try to run away, nor, being what they were, that they would make anything of the noises coming from the bridal bed. Nevertheless…

“It’s the principle of the thing, ” Sam explained as he and the new Mrs. Yeager, accompanied by cheering well-wishers from the Met Lab and from Chugwater, made their way to the house where they’d spend their first night as man and wife. He spoke a little louder, a little more earnestly, than he might have earlier in the day: when they found they were going to host a wedding, the townsfolk had pulled out a good many bottles of dark amber and other fluids.

“You’re right, ” Barbara said, also emphatically. Her cheeks glowed brighter than could be accounted for by the chilly breeze alone.

She let out a squeak when Sam picked her up and carried her over the threshold of the bedroom they’d use, and then another one when she saw the bottle sticking out of a bucket on a stool by the bed. The bucket was ordinary galvanized iron, straight out of a hardware store, but inside, nestled in snow-“Champagne! ” she exclaimed.

Two wineglasses-not champagne flutes, but close enough-rested alongside the bucket. “That’s very nice, ” Yeager said. He gently lifted the bottle out of the snow, undid the foil wrap and the little wire cage, worked the cork a little-and then let it fly out with a report like a rifle shot and ricochet off the ceiling. He had a glass ready to catch the champagne that bubbled out, then finished filling it the more conventional way.

No sooner had the Lancaster’s three-bladed…

“Out of Rochester, or maybe Buffalo, ” van…

“First, I suppose, to confirm what I say-and…

Those trees also concealed Tosevites, as Ussmak…

The Croat ran to the…

“Prepare yourself for immediate departure for…

Even in these times, David Goldfarb had expected…

He went up to the second…

Heinrich Jager gave his interrogator a…

Bobby Fiore almost wished he was still on the…

Vernon, however, kept right on…

Fermi drew out the rods another…

Nevertheless, Molotov owed allegiance not just…

“Still here in Lodz, ” Goldfarb mused. “That’s…

“Assembled shiplords, I…

Morozkin turned to the RAF air crew. “I have-bad…

But no one hung hack or…

Barbara looked at her hands. Her hair tumbled…

Расскажи о сайте: