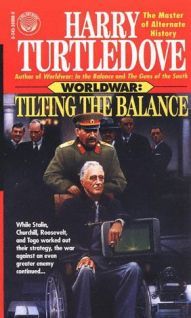

Tilting the Balance

Часть 11

Anielewicz scowled; after what the Nazis had done to the Warsaw ghetto, hearing the word “Jews” in German was plenty to set his teeth on edge all by itself. And Zolraag used it with arrogance of a sort not far removed from that of the Germans. The only difference Anielewicz could see was that the Lizards thought of all humans, not just Jews, as Untermenschen.

“Whose fault is that? ” he demanded, not wanting Zolraag to know he was concerned. “We welcomed you as liberators; we shed our blood to help you take this city, if you’remember, superior sir. And what thanks do we get? To be treated almost as badly under your thumb as we were under the Nazis. ”

“That is not true, ” Zolraag said. “We have given you enough guns to make your fighters the equal of the Armija Krajowa, the Polish Home Army. Where you were below them, we set you above. How do you say we treat you badly? ”

“I say it because you care nothing for our freedom, ” the Jewish fighting leader answered. “You use us for your own purposes and to help make slaves of other people. We have been slaves ourselves. We didn’t like it. We don’t see any reason to think other people like it, either. ”

“The Race will rule this world and all its people, ” Zolraag said, as confidently as if he’d remarked, The sun will come up tomorrow. “Those who work with us will have higher place than those who do not. ”

Before the war, Anielewicz had been a largely secularized Jew. He’d gone to a Polish Gymnasium and university, and studied Latin. He knew what the Latin equivalent of work together was, too: collaborate. He also knew what he’d thought of the Estonian, Latvian, and Ukrainian jackals who helped the German wolves patrol the Warsaw ghetto-and what he’d thought of the Jewish police who betrayed their own people for a crust of bread.

“Superior sir, ” he said earnestly, “with the guns we have from you, we can protect ourselves from the Poles, and that is very good. But most of us would rather die than help you in the way you mean. ”

“This I have seen, and this I do not understand, ” Zolraag said. “Why would you forgo such advantage? ”

“Because of what we would have to do to get it, ” Anielewicz answered. “Poor Moishe Russie wouldn’t speak your lies, so you had to play tricks with his words to make them come out the way you wanted them. No wonder he disappeared after that, and no wonder he made you out to be liars the first chance he got. ”

Zolraag’s eye turrets swung toward him. That slow, deliberate motion held as much menace as if they’d contained 38-centimeter battleship guns rather than organs of vision. “We are still seeking to learn more of these events ourselves, ” he said. “Herr Russie was an associate, even a friend, of yours. We wonder how and if you helped him. ”

“You questioned me under your truth drug, ” Anielewicz reminded him.

“We have not learned as much with it as we hoped from early tests, ” Zolraag said. “Some early experimental subjects may have deceived us as to their reactions. You Tosevites have a gift for being difficult in unusual ways. ”

“Thank you, ” Anielewicz said, grinning.

“I did not mean it as a compliment, ” Zolraag snapped.

Anielewicz knew that. Since he’d been up to his eyebrows in getting Russie away and in making the recording in which Russie blasted the Lizards, he was less than delighted to learn the Lizards had found their drug was worthless.

Zolraag resumed, “I did not summon you here, Herr Anielewicz, to listen to your Tosevite foolishness. I summoned you here to warn you that the uncooperative attitude of you Jews must stop. If it does not, we will disarm you and put you back in the place where you were when we came to Tosev 3. ”

Anielewicz gave the Lizard a long, slow, measuring

No sooner had the Lancaster’s three-bladed props…

Sometimes, in the Warsaw ghetto, Moishe Russie…

The air-raid siren at Bruntingthorpe began…

As helpful as he’d been before, Peary…

Ludmila nodded. Strange, she thought, that an…

The junior officers all…

“Prepare yourself for immediate…

Bunim swung one eye toward the posters while…

He said, “General Chill is willing…

Atvar read intently for a little while,…

But no one hung hack or hesitated. Better…

“Did you hear what he said? ” someone…

“We have decided to produce both explosive metals,…

Heinrich Jager gave his interrogator a dirty…

He knew about shakedowns. His uncle Giuseppe,…

The Croat ran to the next door in, fired…

Even in these times, David Goldfarb…

The general secretary whirled around in…

Расскажи о сайте: